Abstract

Monopolies represent a market structure where a single firm dominates the production and sale of a product with no close substitutes. This article explores the nature of monopolies, their sources, pricing strategies, economic inefficiencies, and the various policy tools used to regulate them. Particular attention is given to natural monopolies, price discrimination, and welfare implications, offering both theoretical foundations and practical applications in industries such as pharmaceuticals and public utilities.

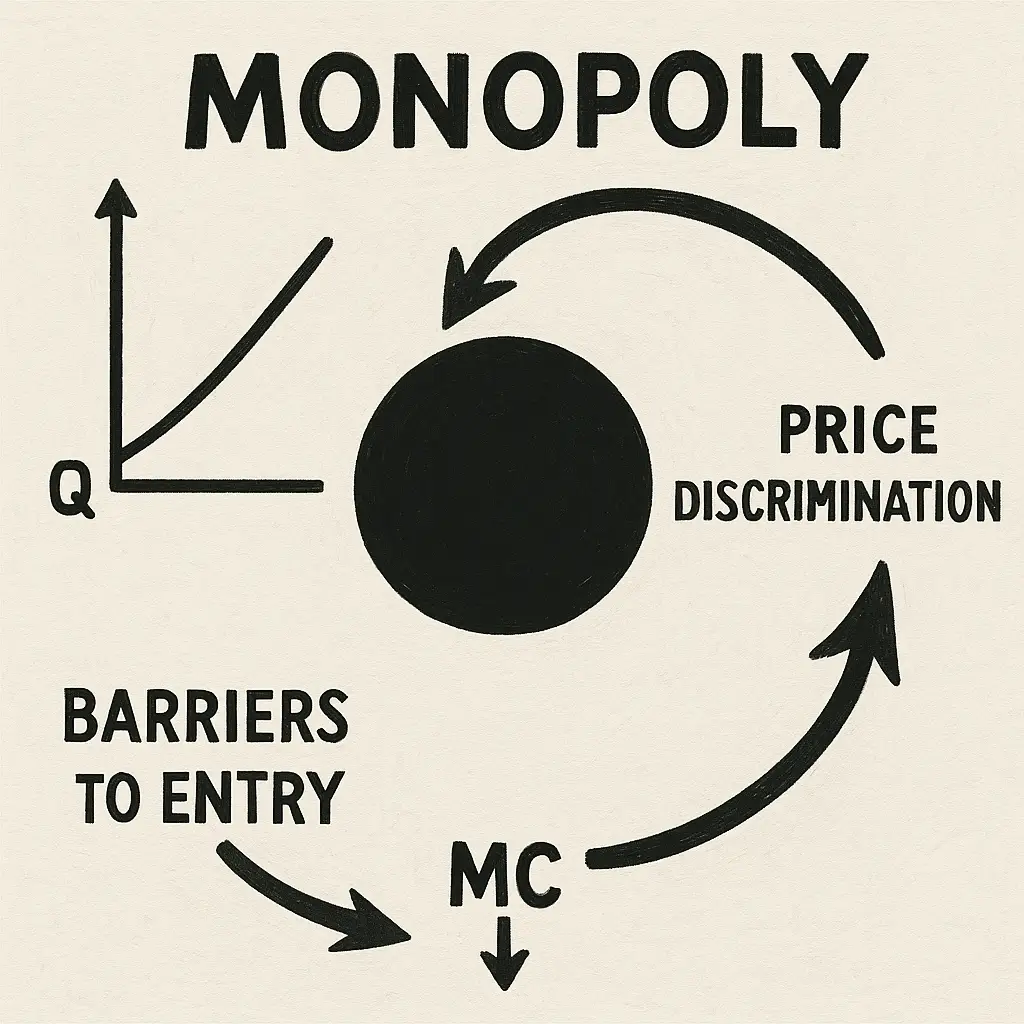

1. Introduction to Monopoly

A monopoly exists when a single company is the exclusive provider of a product or service, and no close substitutes are available. This grants the monopolist significant market power, enabling control over prices and output. Unlike perfectly competitive markets, where numerous firms operate with no pricing power, monopolies can dictate terms, often to the detriment of consumer welfare.

2. Barriers to Entry and Monopoly Formation

Monopolies arise due to significant barriers that prevent other firms from entering the market. These barriers include:

2.1 Exclusive Ownership of Resources

Some firms control critical resources essential for production (e.g., rare minerals), though in practice, such cases are rare.

2.2 Economies of Scale and Natural Monopolies

When a single firm can supply the entire market at a lower cost than multiple firms, it forms a natural monopoly. These occur in industries like water, electricity, or railways where infrastructure costs are high and marginal costs are low.

2.3 Legal Barriers and Government-Granted Monopolies

Patents, copyrights, and exclusive licenses create legal monopolies. Governments may also grant sole rights to firms to operate in specific sectors (e.g., postal services).

3. Revenue and Demand under Monopoly

3.1 Key Revenue Concepts

- Total Revenue (TR) = Price (P) × Quantity (Q)

- Average Revenue (AR) = TR / Q = P

- Marginal Revenue (MR) = ∆TR / ∆Q

Unlike competitive firms, a monopolist’s marginal revenue is always less than the price, due to the downward-sloping demand curve. To sell more units, the monopolist must reduce the price, affecting both marginal and total revenues.

3.2 Demand Curve Characteristics

- A competitive firm faces a perfectly elastic demand curve.

- A monopolist faces the market demand curve, which is downward sloping.

4. Profit Maximization

A monopolist maximizes profit where MR = MC (Marginal Revenue = Marginal Cost). After determining this quantity, the firm uses the demand curve to set the highest price consumers are willing to pay.

Profit (π) is calculated as:

π = TR − TC = (P − ATC) × Q

Where ATC is Average Total Cost.

5. Welfare Implications and Market Failure

5.1 Deadweight Loss

Monopolies restrict output below the socially optimal level, creating a deadweight loss — the loss of welfare due to the difference between what consumers are willing to pay and the monopolist’s cost of production.

5.2 Allocative Inefficiency

Because P > MC in monopoly, the market fails to allocate resources efficiently, resulting in lower consumer surplus and higher producer surplus.

6. Policy Responses to Monopoly Power

Governments employ several strategies to mitigate the negative effects of monopolies:

6.1 Antitrust Legislation

- Prevents mergers that reduce competition

- Breaks up existing monopolies

- Promotes competitive market structures

6.2 Regulation

Governments may regulate prices, especially in natural monopolies, often by setting prices equal to marginal cost to achieve allocative efficiency.

6.3 Public Ownership

Sometimes, the government directly manages monopolies (e.g., nationalized utilities) to ensure fair pricing and service provision.

6.4 Laissez-Faire Approach

In some cases, governments may choose inaction if regulatory intervention is considered less efficient than the market failure itself.

7. Price Discrimination

7.1 Concept

Price discrimination occurs when a monopolist charges different prices to different consumers for the same product, unrelated to differences in production cost.

7.2 Conditions

- Market power

- Ability to segment markets

- Prevention of resale

7.3 Degrees of Price Discrimination

- First-degree (Perfect): Each consumer is charged their maximum willingness to pay.

- Second-degree: Price varies with quantity or product version (e.g., bulk discounts).

- Third-degree: Different groups are charged different prices (e.g., student or senior discounts).

7.4 Welfare Impacts

While price discrimination can increase monopolist profits, perfect price discrimination may reduce deadweight loss by serving all consumers whose willingness to pay exceeds marginal cost.

8. Real-World Application: The Pharmaceutical Market

Patents on pharmaceutical products create temporary monopolies. During the patent period, firms set high prices. After expiration, generics enter, prices fall, and output increases. This scenario highlights both the innovation incentives and the short-run welfare costs of monopolistic pricing.

9. Conclusion

Monopolies present a stark contrast to competitive markets. While they can incentivize innovation and reduce duplication in natural monopolies, they often result in higher prices, lower output, and reduced welfare. Understanding their formation, pricing behavior, and policy responses is essential for crafting effective economic regulations that balance efficiency with equity.

References

- Mankiw, N. G. (2004). Principles of Economics. South-Western.

- Pindyck, R. S., & Rubinfeld, D. L. (2012). Microeconomics. Pearson.

- Varian, H. R. (2014). Intermediate Microeconomics. W. W. Norton & Company.